In an earlier article, Is it Time for a Renaissance in Your Business?, I introduced the concept of “Summit Blindness,” that dangerous condition where a business leader can’t see that they’re at or near the peak of their growth curve. The signs are often there: a creeping sense of sameness in results, a rise in urgent firefighting, and a nagging worry that the playbook isn’t working the way it used to. But recognizing those signals in real time is notoriously hard.

This follow-up asks an even trickier question: Why is it so hard to see the symptoms of Summit Blindness before it’s too late? Why do so many leaders ignore or misinterpret the warning signs until they’re stuck on a plateau, or worse, heading downhill?

The answer lies in the very discipline that built the summit in the first place: optimization.

The optimization trap.

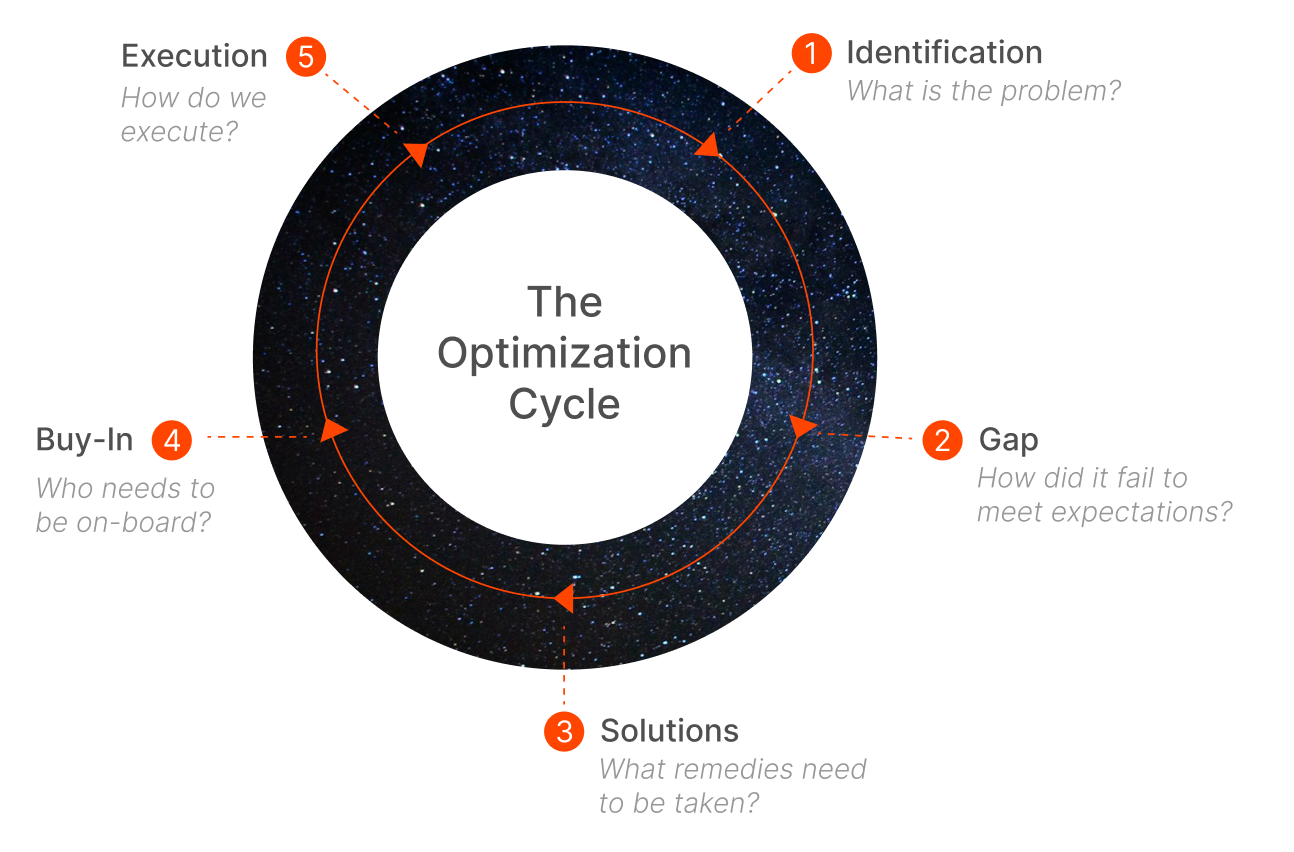

If you’ve led a business for any length of time, you know the optimization cycle by heart: a problem is spotted, the gap measured, recovery actions designed, buy-in secured, execution delivered.

Then rinse and repeat.

This cycle works so well we barely think about it. It’s the unspoken operating system of business management. It’s how you climbed the summit: refining, streamlining, and maximizing until the machine hummed.

But here’s the problem: everything eventually taps out. Every market, product, and business model has a natural life cycle. Physics reminds us that what goes up must level off—and eventually break down. When you reach your growth curve plateau, the very engine that fueled your growth—that optimization cycle—becomes a trap.

Yet, instead of questioning their approach, leaders double down, escalating the same optimization cycle but with greater intensity: Fire the sales leader. Hire a new agency. Demand a miracle quarter. It feels bold. But in truth, it’s just a louder version of the same loop. Optimization got you here. But it won’t get you there.

I’ve seen this play out firsthand. A CEO, panicked by a stall, fires a capable leader. Not because the talent failed, but because the structure did. The truth is, no one could have delivered, because the challenge wasn’t about talent. It was about the underlying structure. But in the grip of Summit Blindness, the fast answer often feels safer than the deep one.

If optimization can’t take you further, why do leaders cling to it? The answer lies not in strategy, but in psychology.

Why we stay in the trap.

If you think this sounds obvious in hindsight, you’re right. But in the moment, it’s anything but. That’s because we aren’t just operating on strategy. We’re also operating on psychology.

Neuroscientist Gregory Berns once described the brain as a “lazy piece of meat.” By instinct, we prefer the known to the unknown, the routine to the unexpected. The mind craves predictability, and the optimization loop scratches that itch beautifully.

Unfortunately, the same cognitive shortcuts that help us act decisively in familiar conditions can blind us to change when the ground is shifting. Here are some of the mental traps that keep leaders stuck:

- Sunk cost fallacy – We overvalue past investments, refusing to pivot because we’ve “already spent so much” on the current strategy.

- Status quo bias – We assume the safest bet is to stick with what’s familiar, even when the environment has changed.

- Confirmation bias – We seek data that validates our current approach and dismiss signals that something fundamentally new is required.

- Overconfidence effect – Past success makes us overestimate our ability to muscle through a plateau with sheer execution.

- Availability bias – Recent experiences loom larger in our minds, so a strong quarter convinces us the decline isn’t real.

These biases don’t just cloud judgment, they reinforce the optimization cycle itself. We become trapped in the comforting rhythm of problem/solution/execute, blind to the fact that the real problem isn’t a gap in execution. It’s a gap in how we think about correcting the problem.

How to escape the trap.

Escaping the optimization trap doesn’t require a wholesale rejection of optimization. It’s still essential. But it does require recognizing when the rules of the game have changed.

Here are some questions leaders can ask to check whether Summit Blindness is taking hold:

- Are we solving the same problems with increasing urgency but diminishing returns?

- Are we reacting to symptoms (flat sales, longer cycles) without questioning structural causes (market saturation, relevance of our offer)?

- Are we changing players on the team more often than changing the playbook?

- Do we have more activity but less momentum?

If the honest answer is “yes” to any of these, it may be time to look beyond optimization.

That’s where the three levers of transformational growth come in:

- Resonant Market Focus – Are we still aimed at the right customers with the right clarity of who we serve best?

- Bold Offer – Is our value proposition compelling enough to create intrigue, not just interest?

- Robust Revenue Engine – Do our processes, teams, and insights align to sustain growth, or are we just adding fuel to a leaky system?

These levers shift the game from squeezing efficiency out of the current model to reimagining the model itself. They create new momentum when optimization alone has run its course.

The courage to start a new ascent.

Summit Blindness is dangerous not because the signs aren’t there, but because our own minds keep us from seeing them. The optimization cycle feels safe, familiar, and controllable. Until it isn’t.

Escaping the trap takes courage; the courage to question the very playbook that made you successful, and the clarity to see when it’s time to trade optimization for transformation.

Fresh eyes often make the difference. An advisor not conditioned by your operating paradigm can see opportunities you can’t. Not because they’re smarter, but because they aren’t blinded by the summit you’ve worked so hard to climb.

That’s why I do this work. If you sense that Summit Blindness may be setting in, I’m here to help you see beyond the optimization trap and chart a new ascent. Because the true measure of leadership isn’t reaching the summit. It’s having the courage to find a new mountain to climb.

%20(1).jpg)